De la Tour's Siren: Difference between revisions

ArxCyberwolf (talk | contribs) (Moved page over from the CDS Wiki.) |

ArxCyberwolf (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

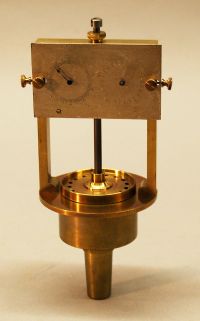

{{Infobox siren|title=De la Tour's Siren|company=Charles Cagniard de la Tour|produced=1819-1859?|type=[[Omnidirectional]] [[Electromechanical]]}} | {{Infobox siren|title=De la Tour's Siren|company=Charles Cagniard de la Tour|produced=1819-1859?|type=[[Omnidirectional]] [[Electromechanical]]|image=De_la_tour_siren.jpg|caption=An example of a De la Tour siren.}} | ||

'''De la Tour's siren''' (or sirène) was an early mechanical siren produced by the French engineer Charles Cagniard de la Tour in 1819.<ref>[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siren_(alarm) Siren (alarm)] from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia</ref> Largely considered one of the first rotor and stator sirens to be made, it used a bellows apparatus to force air through its rotor. As the air passed through the ports of the stator, it produced a series of regular pressure waves that is perceived as a musical tone. The siren's pitch could be raised or lowered by simply increasing or decreasing the speed of the rotor via the dials on the siren. Connected by gears to the rotor's shaft, they recorded the number of times the rotor spun. This was important because simply multiplying the number of rotations per second by the number of ports in the stator gave the precise frequency of the tone being produced. For the first time, scientists were now able to create tones of specific frequencies and measure the frequencies of other sounds by comparing them to the measurable sounds of the siren. As acoustic research developed, several important improvements were made to the siren, and it continued to be an important scientific tool into the early 20th century. | '''De la Tour's siren''' (or sirène) was an early mechanical siren produced by the French engineer Charles Cagniard de la Tour in 1819.<ref>[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siren_(alarm) Siren (alarm)] from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia</ref> Largely considered one of the first rotor and stator sirens to be made, it used a bellows apparatus to force air through its rotor. As the air passed through the ports of the stator, it produced a series of regular pressure waves that is perceived as a musical tone. The siren's pitch could be raised or lowered by simply increasing or decreasing the speed of the rotor via the dials on the siren. Connected by gears to the rotor's shaft, they recorded the number of times the rotor spun. This was important because simply multiplying the number of rotations per second by the number of ports in the stator gave the precise frequency of the tone being produced. For the first time, scientists were now able to create tones of specific frequencies and measure the frequencies of other sounds by comparing them to the measurable sounds of the siren. As acoustic research developed, several important improvements were made to the siren, and it continued to be an important scientific tool into the early 20th century. | ||

Latest revision as of 22:59, 16 October 2024

| De la Tour's Siren | |

An example of a De la Tour siren. | |

| Company | Charles Cagniard de la Tour |

|---|---|

| Produced | 1819-1859? |

| Type | Omnidirectional Electromechanical |

De la Tour's siren (or sirène) was an early mechanical siren produced by the French engineer Charles Cagniard de la Tour in 1819.[1] Largely considered one of the first rotor and stator sirens to be made, it used a bellows apparatus to force air through its rotor. As the air passed through the ports of the stator, it produced a series of regular pressure waves that is perceived as a musical tone. The siren's pitch could be raised or lowered by simply increasing or decreasing the speed of the rotor via the dials on the siren. Connected by gears to the rotor's shaft, they recorded the number of times the rotor spun. This was important because simply multiplying the number of rotations per second by the number of ports in the stator gave the precise frequency of the tone being produced. For the first time, scientists were now able to create tones of specific frequencies and measure the frequencies of other sounds by comparing them to the measurable sounds of the siren. As acoustic research developed, several important improvements were made to the siren, and it continued to be an important scientific tool into the early 20th century.

De la Tour's siren was used to answer a variety of other scientific questions. He used it not only to measure musical frequencies, but also the speed of a mosquito’s wings (10,000 flutters per second). He showed that it worked as a warning signal on ships (which kickstarted the use of sirens as warning devices) and reported that it even made a sound underwater (using water pressure instead of air pressure). His siren was later used to measure the speed of sound in water, and it was this property of “being sonorous in the water” that caused him to call it a "siren".

One of the advantages of De la Tour’s siren was that it was simple and compact. The same air pressure that made the sound was also used to drive the rotor. This was accomplished by drilling the holes in the rotor and stator obliquely, at such angles that the rotor begins to spin automatically, much like a turbine, when air pressure is applied. However, this same feature caused one of the siren’s problems. Because it was driven by the same air pressure that produced the sound, producing higher tones on the siren required more air pressure – which meant that the sound would also be louder. The opposite was true for lower notes. De la Tour recorded the siren was quieter and softer on low notes and louder and shrill on high notes. In terms of making actual measurements, the siren was also limited by its reliance on human hearing. Under ideal conditions, a skilled researcher could use De la Tour’s siren to distinguish between sounds that were a fraction of a wavelength apart.

External links

- ↑ Siren (alarm) from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia